Eurocrisis: Its Baack!

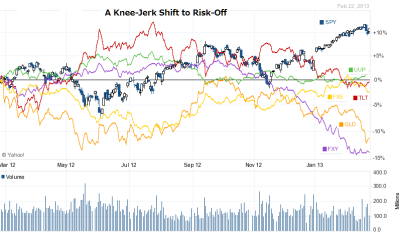

While it never really went away, Italian voters put the Eurozone’s problems on the front pages again after anti-austerity parties appeared on track to win a majority of seats in the Italian parliament, vastly complicating efforts to forge a government able to carry through EU-imposed reforms. This plus a looming US sequestration forced investors to take another look at risk as US stocks attempted to reach pre-crisis highs. The sharp surge in the S&P 500 VIX volatility index shows just how much of a negative surprise the Italian elections were. With one Mario (Monti) gone, investors are beginning to wonder if the other Monti (Draghi) can pull another rabbit from the ECB’s hat to quell Eurozone concerns. The Italian elections sent EUR plunging against USD and JPY, triggering profit-taking in US stocks, and threatening to derail the weak JPY-driven rally in Japan stocks.

Investors may now take a step back to see just how much the Italian elections hurt the bailing wire and duck tape countermeasures that had so far kept a lid on Euro-crisis, and just how much economic pain the US sequestration political boondoggle in the US causes, and just how serious the Fed is taking concerns about the future risk of normalizing its over-swollen balance sheet.

As we pointed out in

market sentiment indicators flashing yellow/red, sentiment indicators were already signalling that US stocks were due for a correction, with increasingly nervous investors waiting for an excuse to take profits. For the time being, however, bulled-up investors are mainly viewing the new developments as a somewhat welcome a “speed bump” pause in the stock rally, i.e., a chance for those who missed most of the move since last November to participate in the rally. How long this “buy on weakness” depends on how resilient stocks are over the next few weeks.

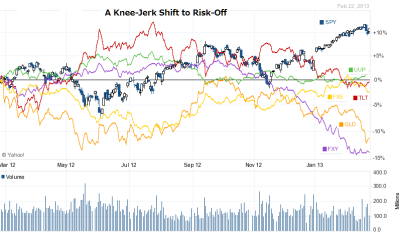

The knee-jerk reaction so far has been classic risk-off, i.e., stocks fell, USD rose, EUR fell and sell-off in JPY temporarily reversed as US bond yields up-ticked and even Gold got a bid. As the short JPY technically was also over-extended, an unwinding of speculator short JPY positions could see JPY test JPY90/USD resistance, thereby stunting the Nikkei 225’s sharp rebound, at least for the time being.

|

| Source: Yahoo.com |

Warnings of Dire Consequences of Massive Government Debt and Swollen Central Bank Balance Sheets

Lurking in the background is a big picture concern. The West faced a 1931 moment in late 2008. The cost of avoiding a 1931 moment has been soaring government debt and economies that are too weak to support growing entitlement costs, which in the U.S. are expected to grow to $700 billion over the next four years, according to hedge fund legend Stanley Druckenmiller. While Druckenmiller believes there is still time to tackle the U.S. debt issue, he warns that if it is not dealt with in the next four or five years, “we’re going to wake up, interest rates are going to explode and the next generation is going to have a tough time.”

The irony is that the U.S. is the least dirty shirt in the closet. Even former EU commissioner Frits Bolkestein is among a crowd of investors convinced that a break-up of the sovereign debt-challenged Euro was inevitable, and speculators mercilessly pounded Greece, Spain, Italy and other southern European bonds until Mario Draghi put the hounds at bay by promising to “do whatever it takes” to save the Euro. Japan has long been on the short list of countries expected to see fiscal crisis for several years now, ostensibly as they have already crossed the debt spiral rubicon, according to absolutely convinced hedge fund managers like Kyle Bass.

Scare Stories are Currently Not Affecting How Investors are Making Asset Allocation Decisions

But even Druckenmiller admits the debt problem doesn’t change how investors currently make asset-allocation decisions. “(Because) the Fed printing $85 billion a month, this is not an immediate concern…but this can’t go on forever.” That said, most professional investors are having trouble assimilating such imminently reasonable scenarios with soaring stock markets, the performance in which they ostensibly get paid. Consistently profitable hedge fund maven Ray Dalio says 2013 is likely to be a transition year, where large amounts of cash—ostensibly previously parked in safe havens—will move to stock and all sorts of stuff – goods, services, and financial assets.

At the same time, these same investors have little real confidence in the economic recovery upon which rising financial assets are supposedly predictated, and have wavered between “risk on” and “risk off” on several occasions since the March 2009 post crisis secular low in stock prices. On the past two occasions, the prospect of central banks backing away from extraordinary monetary policy has been enough to send them scurrying back into risk off mode, only to venture out again as central banks again re-assure that they are on the case.

Nevertheless, supported by Fed assurances of “unlimited” QE, ECB assurances that they will do whatever it takes, and the prospect of the BoJ joining the full-scale balance sheet deployment party, US stock prices are near pre-2008 crisis highs hit in 2007, and growing investor complacency saw the S&P 500 VIX volatility (fear) index recently hitting its lowest point since May 2007.

But Complacency Makes Some People Nervous…

But investor complacency itself is cause enough to make some investors worried. After the S&P 500 VIX volatility index hit its lowest point since May 2007, investors were temporarily spooked last week by indications in the FOMC minutes that “many participants…expressed some concerns about potential costs and risks from further asset purchases.” The balance sheet risk issue first surfaced in the December FOMC, but was papered over by the launch of a $45 billion program to buy longer-dated TBs, and the continuance in the January meeting of $85 billion of purchases until the labor market improved “substantially” in the context of price stability around the 2% level.

…And FOMC Fretting about Fed Balance Sheet Risk is Downright Disturbing

Thus while hard money proponents have long warned of “wanton” and “dangerous” money printing, even FOMC members are beginning to fret about the growing risk its swollen balance sheet poses in the inevitable process of normalizing the size and composition of its balance sheet.

In other words, the really tricky part for stock markets is when central banks are confident enough in the economic recovery, ostensibly an “all clear” sign to investors worried about the sustainability of the recovery, to attempt normalizing their balance sheets.

Nearly everyone recognizes that the first round of global QE prevented/forestalled financial collapse. But successive rounds of QE have demonstrably diminishing returns versus growing risks of swollen central bank balance sheets, a tidbit that financial markets are so far blithely ignoring. Specifically, the three key issues underlying the debate about burgeoning government debt swollen central bank balance sheet are:

a) How long the fiscal path of governments can be sustained under current policies.

b) If governments cannot or will not service this debt, central banks may be ultimately forced to choose between inflation spiral-inducing debt monetization, or in idely standing by as the government defaults.

c) Central bank balance sheets are currently extremely large by historical standards and still growing, and the inevitable process of normalizing the size and composition of the balance sheet poses significant uncertainties and challenges for monetary policymakers.

The 90% Solution and Debt Sustainability

Even Paul Krugman cannot deny that excessive government debt has consequences. Reinhart and Rogoff (2012) documented that levels of sovereign debt above 90% of GDP in advanced countries lead to a substantial decline in economic growth, while Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli (2011) found a threshold of around 85% for the debt-to-GDP ratio at which sovereign debt retards growth. Such data were the inspiration for “new normal” scenarios, which posited that potential economic growth would semi-permanently shift downward following the 2008 crisis as economies delivered.

Furthermore, debt default is a clear and present danger. Greenlaw, Hamilton, Hooper and Mishkin (2013) as well as other studies observe that, since the more government debt is held by foreigners, the greater the political incentives to default on that debt, and therefore the greater perceived risk of this debt, which raises borrowing costs. Further, higher overall foreign debt—both public and private—also makes it more difficult for a country to continue making interest payments on sovereign debt, thus increasing perceived risk and the interest rate demanded for this risk. Current-account deficits are also highly significant; i.e., a country that increases its current-account deficit to GDP would be expected to face higher interest rates demanded for holding sovereign debt.

The bottom line of such research is that, the larger the debt to GDP, the harder it is for a country to “grow” out of its debt, while high levels of sovereign debt held by foreigners in combination with high and consistent current account deficits greatly increases the risk of triggering a fiscal and/or currency crisis. The “great divide” in economic thinking is what should we be doing about it now. The Keynesians say continue throwing fiscal spending at the problem, and worry about the debt after the economy recovers. The monetarists say keep pushing on extraordinary monetary policy. The hard money traditionalists say both policies are a prescription for a renewed, deeper crisis, and that we only have a few years to act to reduce debt.

Investors, whose careers have been based on the maxim that “price is truth”, say this heavy intervention has already seriously skewed the market pricing mechanism, It is also gut-level clear there are limits to how much fiscal spending governments and how much balance sheet deployment central banks can continue in the face of massive and growing debt. Problem is, no one knows exactly where these limits are. The only certainty is the extreme aversion to finding out; on the part of governments, central bankers and investors. Ostensibly, central banks could continue printing money and expanding their balance sheets indefinitely, but there is a good reason for the historically strong adversion to full-scale debt monetization by central banks, and that is again fiat currency debasement and runaway inflation.

How Damaging the Risk of Fed Balance Sheet Losses?

A recent paper by Greenlaw, Hamilton, Hooper and Mishkin (2013) stimulated debate in the Federal Reserve about the risk of losses on asset sales and low remittances to the Treasury, and how this could lead the Federal Reserve to delay balance sheet normalization and fail to remove monetary accommodation for too long, exacerbating inflationary pressures.

Monetarists argue that losses on the Fed balance sheet are an accounting irrelevancy.

While the value of bond holdings in swollen (USD 3 trillion) bond holdings in central bank balance sheets would get crushed along with bond-heavy financial institution portfolios, ostensibly reversing current unrealized gains of some USD200 billion to an unrealized loss of USD300 billion. The Fed’s contributions to the Treasury, which have reduced the annual deficit by some 10% over the past few years, would fall to zero. Monetarists claim the magnitude of such a change (USD 80 billion) ostensibly would not be that big a deal. An accounting “asset” could simply be created equal to the annual loss, in the form of a future claim on remittances to Treasury.

Thus far, the Federal Reserve’s asset purchases have actually increased its remittances to the Treasury, at an annual level of about $80 billion from 2010 to 2012. These remittances are any rate are likely to approach zero as interest rates rise and the Fed balance sheet normalizes. But Bernanke and other central bankers are not monetarists, and what matters is what the central bankers think.

In recent public remarks, Governor Jerome H. Powell quotes historical precedent in playing down these risks. Federal debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) increased significantly on two prior occasions in modern history–during the Great Depression-World War II era and, to a smaller extent, the two decades ending in the mid-1990s. In each case, fiscal policy responded by running sustained primary surpluses and reducing debt to levels below 40% of GDP. Thus the party line is, “the foundation of U.S. debt policy is the promise of safety for bondholders backed by primary surpluses only in response to a high debt-GDP ratio,” While this is the principal reason why the federal debt of the United States still has the market’s trust, no one wants to contemplate the consequences of the US Treasury or the Fed losing the market’s trust.

Growing Probability of a 1994 Bond Scenario?

When Druckenmiller says, “we’re going to wake up, interest rates are going to explode and the next generation is going to have a tough time,” he is talking about a sharp backup in bond yields, aka the so-called 1994 scenario, or worse. Ostensibly, any whiff of inflation would cause a bond market rout, leaving not only escalating losses on the Fed’s trillions of USD in bond holdings, but also wrecking havoc with private sector financial institution balance sheets. The longer the Fed keeps pumping away under QE, the greater the ostensible risk. Under Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, yields on 30yr treasuries jumped 240bps in a nine-month time span, that is seared into the memories of bond-holders. Talk of a “Great Rotation” from bonds into equities elicits the same painful memories.

Great Rotation as a Process Rather than an Event

Current market signals in the U.S., U.K. and Japan bond markets do not suggests that these countries are near the point of losing the market’s confidence, or that the bond market is “smelling” something afoot. More reasonable sounding scenarios come from people like veteran technical analyst Louise Yamada, who like Ray Dalio see a potential turning point comparable to 1946 when deflation was defeated and the last bear market in bonds began. Her point, which by the way we agree, is that the Great Rotation is likely to be a slow process, characterized by a “bottoming process in rates, or a topping process in price”.

Alarmists Can’t Have it Both Ways

The alarmist scenarios are internally inconsistent. On the one hand, they insist that the Fed’s (and other central bank) unconventional policies are not working to restore sustainable growth, and that central banks in desperation at the prospect of potential sovereign default, will be forced into full-scale debt monetization. On the other, they warn of a bond market rout, ostensibly on a recovery sufficient for these same central banks to attempt to “normalize” their balance sheets and a “great rotation” from bonds into equities, which is a big “risk on” trade if there ever was one.

Worry About the U.K. First….

If investors closely examined the academic work on past periods of excess sovereign debt, they would be more worried about a fiscal crisis/currency crash in the U.K. rather than Japan. The punch line of said research is, to repeat, that debt-to-GDP over 90% chokes off economic growth, which certainly happened in Japan, but is now happening in the UK, Euroland and the US. The larger the debt to GDP, the harder it is for a country to “grow” out of its debt, while all-out austerity only ensures a more rapid deterioration in debt relative to the economy, and all the more central bank money printing to stave off the ravaging effects of this austerity—true for both Euroland, the UK and the US.

Further, high levels of sovereign debt held by foreigners in combination with high and consistent current account deficits greatly increases the risk of triggering a fiscal and/or currency crisis. This factor is not relative to the case of Japan, where foreign ownership of debt is minimal and the current account deficit is a very recent phenomenon.

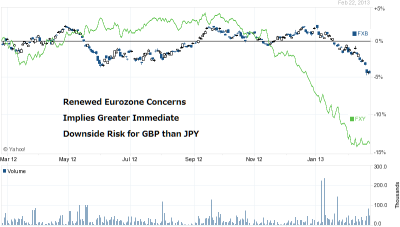

JPY and GBP are currently the favorite currencies to short among currency traders. While the Japanese government has gained more notoriety for reflationary “Abenomics” and their wish to see JPY much cheaper, the UK authorities are if anything just as keen to see GBP much cheaper. While not as obvious about it, UK fiscal and monetary authorities are just as keen to see a weaker pound sterling. Ben Broadbent, yet another former Goldman Sachs banker and BoE Monetary Policy Committee member, stated that a weak pound will be necessary for some time to rebalance the economy towards exports. FT economist Martin Wolff observed, “sterling is falling, Hurray!”. BoE governor Mervyn King proposed 25 billion pounds of further asset purchases, but was voted down. Not to be deterred, in February he said the U.K.’s recovery may require a weaker pound, right after a G7 statement to “not engage in unilateral intervention” on currencies. Governor King has also stated that countries had the right to pursue stimulus, regardless of the exchange rate consequences, while brushing off the potential negative side effects on inflation. In fact, the only difference between Japan’s and the UK’s efforts to depreciate their currencies is that the UK is more adept at sending the signal.

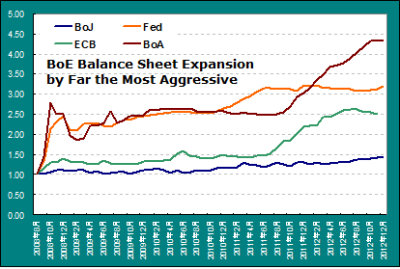

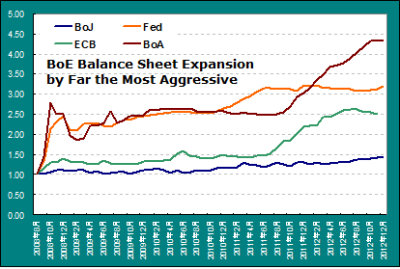

In terms of actual central bank action, the UK since 2010 has been expanding its balance sheet at a much more rapid rate than both the Fed, the ECB and certainly the BoJ.

|

| Source: Japan Investor, respective central banks |

Big Market Reaction to UKDowngrade by Moody’s

While the USD and JPY barely twitched when the respective countries’ sovereign debts were downgraded by rating agencies, the negative reaction in GBP was very noticeable, and GBP is now just as much a target of currency shorts as JPY is. While the dour economic mood in Tokyo has lifted dramatically with Abenomics, Moody’s sees continued weakness in the U.K.medium-term economic outlook extending into the second-half of this decade, given the drag on growth from the slow growth of the global economy, and from ongoing domestic public and private sector deleveraging, despite a committed austerity program. Indeed, the UKgovernment’s ability to deliver savings through austerity as planned is now in doubt.

Then there is the UK’s total debt position. Including financial sector debt, UKdebt to GDP is over 900%, which makes Japan’s 600%-plus look relatively mild in comparison, and the US 300%-plus look rather small. Higher overall foreign debt—both public and private—also makes it more difficult for a country to continue making interest payments on sovereign debt, thus increasing perceived risk and the interest rate demanded for this risk. Like the US, UK national debt has increased sharply because of, a) the recession, b) an underlying structural deficit, and c) costs of a bailout of the banking sector.

So far, the UK’s current debt position is that it hasn’t led to a rise in government bond yields, because pound sterling looked absolutely safe compared to a very shaky Euro. The Centre for Policy Studies argues that the real national debt is actually more like 104% of GDP, including all the public sector pension liabilities such as pensions, private finance initiative contracts, and Northern Rock liabilities. The UK government has also added an extra £500bn of potential liabilities by offering to back mortgage securities, where in theory they could be liable for extra debts of up to £500bn.

High Foreign Ownership of Debt

While the Bank of England owns nearly 26% of this debt, a big chunk, nearly 31% is owned by foreigners. But by far the biggest component of UK external debt is the banking sector. While the debt in the banking sector reflects the fact the UK economy is very open with an active financial sector and free movement of capital, the nationalization of some of the U.K.’s biggest financial institutions has shown that these debts in a pinch have a high probability of becoming government debts through nationalization. John Kingman, boss of UK Financial Investments, has stated, “No one can say a system is mended when the bulk of bank lending is dependent on huge government guarantees and where the government is the main shareholder.” BoE governor Mervyn King has also stated that ongoing Eurozone crisis is a “mess” that poses the “most serious and immediate” risk to the UKbanking system,

External debt to GDP alone is some 390% of GDP for the UK. and nearly four times that of Japanin absolute value. Further, Japan is the world’s largest net international creditor and has been for nearly 20 years, while the U.K. is a net international debtor. While USD is still the prominent reserve currency for central banks (at some 62%), GBP and JPY are essentially the same (at 4%-plus), meaning there is no special inherent support for GBP from central banks like USD, EUR or German mark.

Bank of England policymaker Adam Posen in 2010 outlined the very real risk to UK banks from the Euro crisis, as 60% of UK trade is with the Eurozone. The Bank of England has been pushing UK banks to shore up their capital positions, as the indirect exposures to Euro risk were “considerable”, and has been pushing UK banks to cut their exposure to this risk. Outgoing BoE governor Mervyn King went so far as to say the risk was still “severe” in late 2012 in a letter to Chancellor George Osborn, and pushed for further BoE asset purchases, but was voted down.

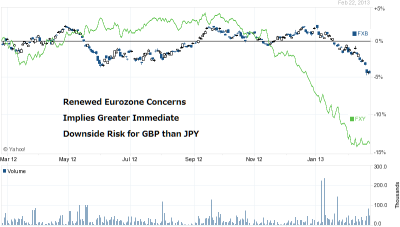

Thus while the short JPY trade has been front and center on traders’ radar since Abenomics hit the scene, GBP may have more downside for the foreseeable future as investors are reminded that the Euro crisis is far from over.

|

| Source: Yahoo.com |